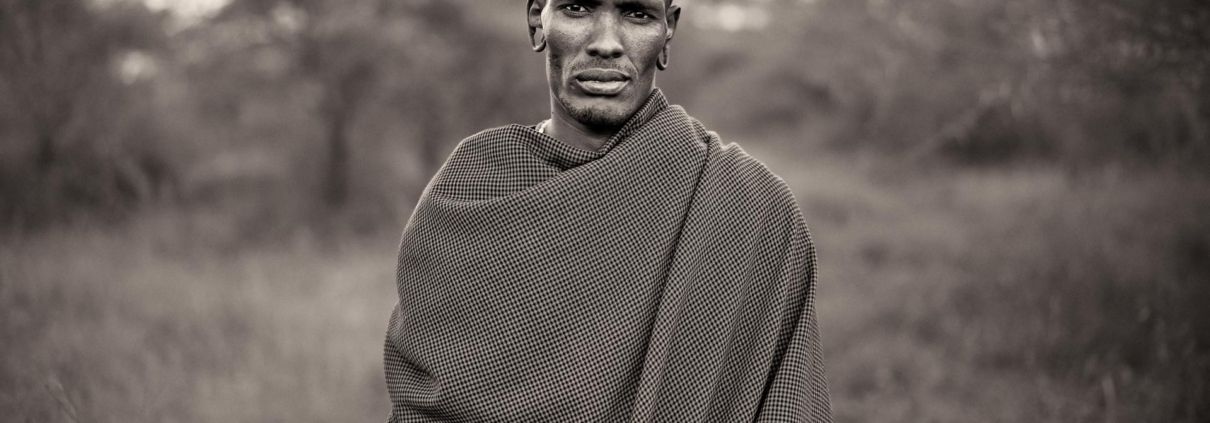

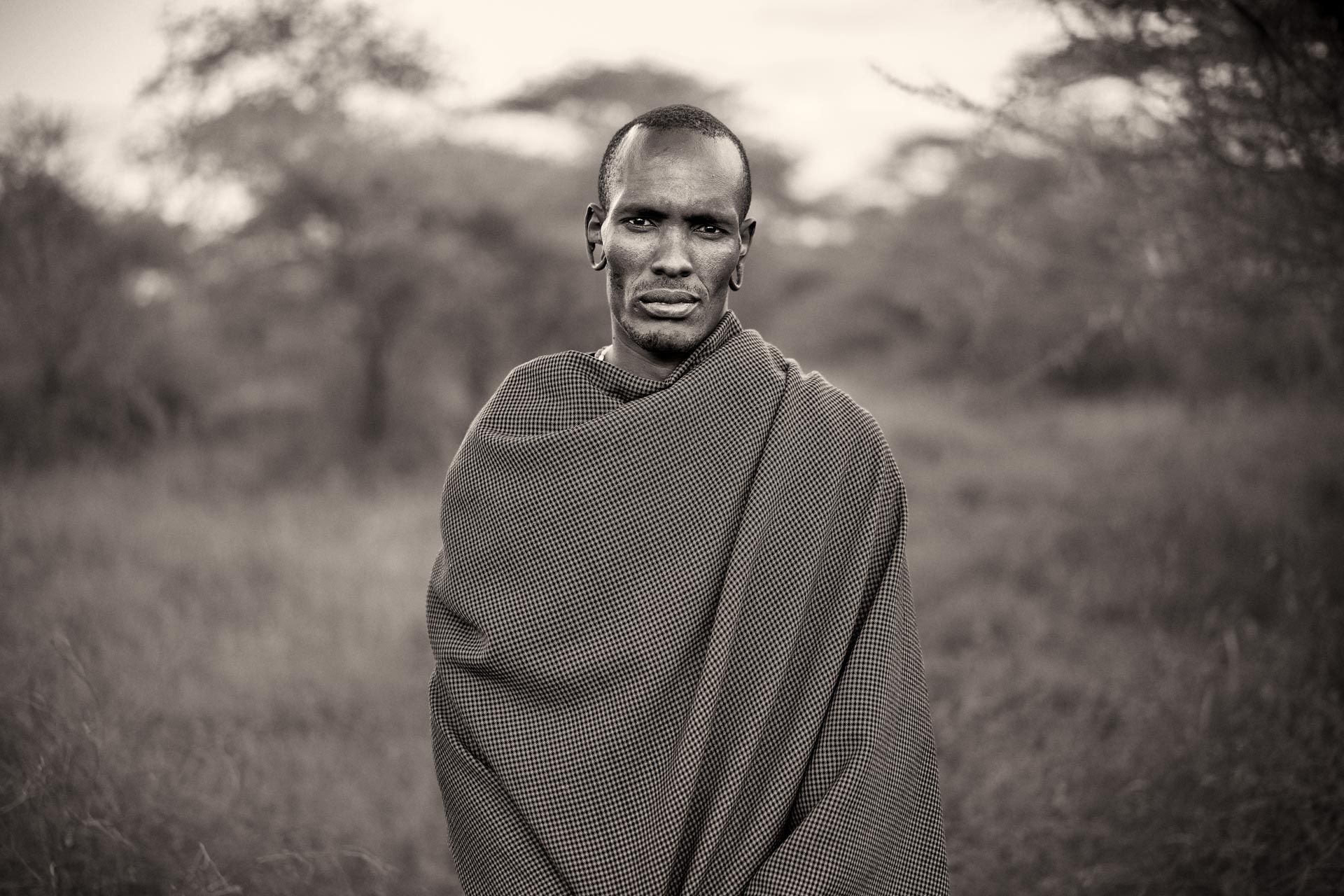

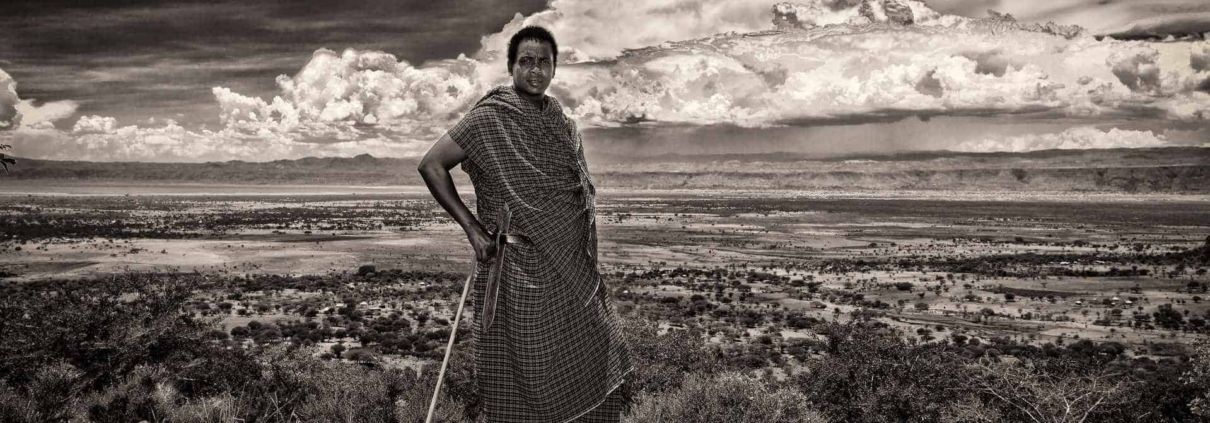

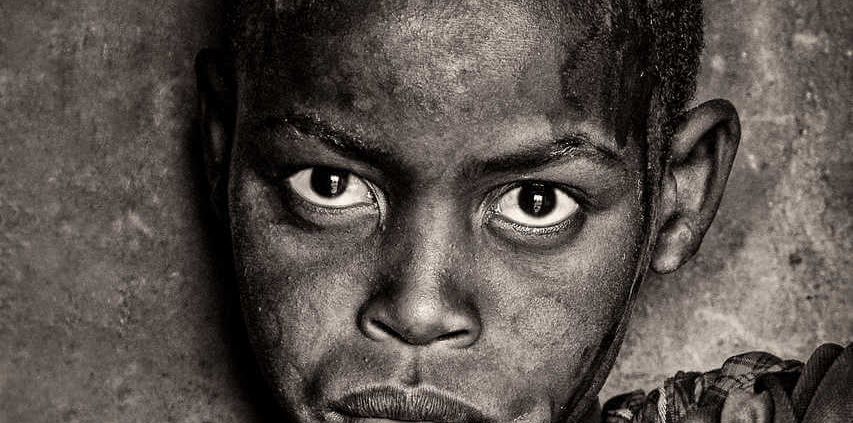

The Maasai – Gold Medal, 2019 North Shore Salon of Photography: Portrait category, print

The Maasai inhabit the African Great Lakes region and arrived via the South Sudan. The Maasai are famous for their fearsome reputations as warriors and cattle-rustlers. Maasai society is strongly patriarchal in nature, with elder men, sometimes joined by retired elders, deciding most major matters for each Maasai group. A full body of oral law covers many aspects of behavior. Formal execution is unknown, and normally payment in cattle will settle matters. An out-of-court process is also practiced called ‘amitu’, ‘to make peace’, or ‘arop’, which involves a substantial apology. The monotheistic Maasai worship a single deity called Enkai or Engai. Engai has a dual nature: Engai Narok (Black God) is benevolent, and Engai Na-nyokie (Red God) is vengeful. There are also two pillars or totems of Maasai society: Oodo Mongi, the Red Cow and Orok Kiteng, the Black Cow with a subdivision of five clans or family trees. The maasai also has a totemic animal which is the lion however, the animal can be killed. The way the Maasai kill the lion differs from trophy hunting as it is used in the rite of passage ceremony. The “Mountain of God”, Ol Doinyo Lengai, is located in northernmost Tanzania and can be seen from Lake Natron in southernmost Kenya. The central human figure in the Maasai religious system is the laibon whose roles include shamanistic healing, divination and prophecy, and ensuring success in war or adequate rainfall. Today, they have a political role as well due to the elevation of leaders. Whatever power an individual laibon had was a function of personality rather than position. Many Maasai have also adopted Christianity and Islam. The Maasai are known for their intricate jewelry.

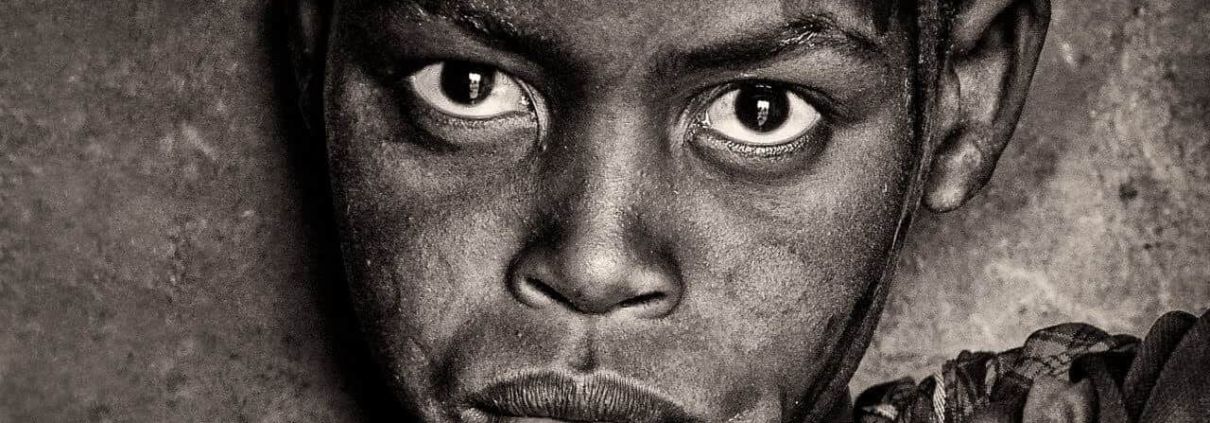

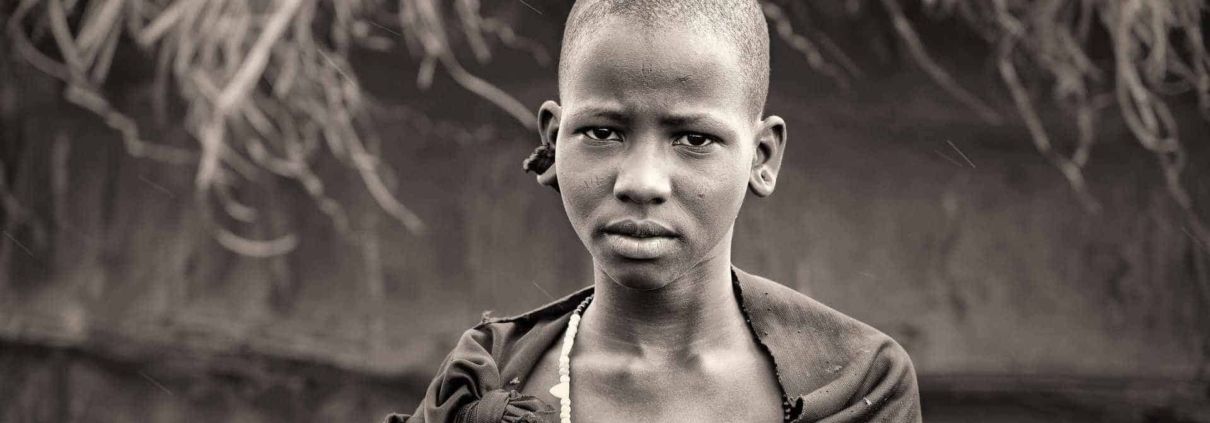

The piercing and stretching of earlobes is common among the Maasai as with other tribes. Various materials have been used to both pierce and stretch the lobes, including thorns for piercing, twigs, bundles of twigs, stones, the cross section of elephant tusks and empty film canisters.

As a historically nomadic and then semi-nomadic people, the Maasai have traditionally relied on local, readily available materials and indigenous technology to construct their housing. The traditional Maasai house was in the first instance designed for people on the move and was thus very impermanent in nature. The houses are either somewhat rectangular shaped with extensions or circular, and are constructed by able-bodied women.

The structural framework of a typical hut is formed of timber poles fixed directly into the ground and interwoven with a lattice of smaller branches wattle, which is then plastered with a mix of mud, sticks, grass, cow dung, human urine, and ash. The cow dung ensures that the roof is waterproof. The enkaj or engaji is small, measuring about 3 × 5 m and standing only 1.5 m high. Within this space, the family cooks, eats, sleeps, socializes, and stores food, fuel, and other household possessions. Small livestock are also often accommodated within the enkaji. Villages are enclosed in a circular fence (an enkang) built by the men, usually of thorned acacia, a native tree. At night, all cows, goats, and sheep are placed in an enclosure in the centre, safe from wild animals.

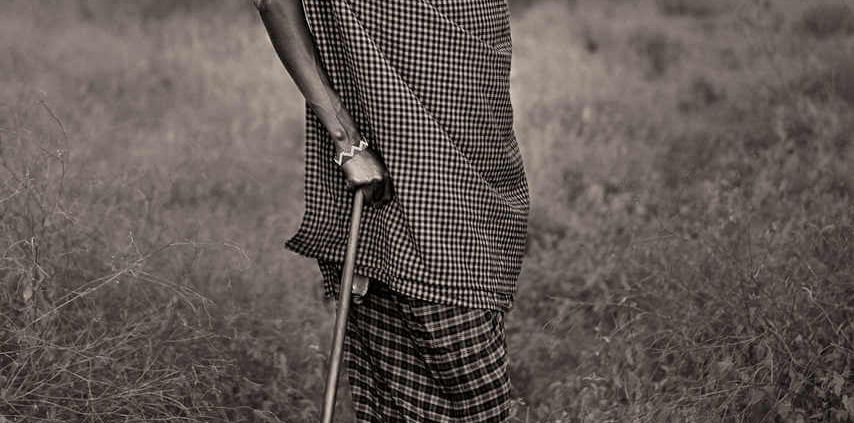

Shúkà is the Maa word for sheets traditionally worn wrapped around the body. These are typically red, though with some other colors such as blue and plaid patterns. Pink, even with flowers, is not shunned by warriors. One piece garments known as kanga, a Swahili term, are common. Maasai near the coast may wear kikoi, a type of sarong that comes in many different colors and textiles. However, the preferred style is stripes.

Many Maasai in Tanzania wear simple sandals, which were until recently made from cowhides. They are now soled with tire strips or plastic. Both men and women wear wooden bracelets. The Maasai women regularly weave and bead jewellery. This beadwork plays an essential part in the ornamentation of their body. Although there are variations in the meaning of the color of the beads, some general meanings for a few colors are: white, peace; blue, water; red, warrior/blood/bravery.

Beadworking, done by women, has a long history among the Maasai, who articulate their identity and position in society through body ornaments and body painting. Before contact with Europeans, the beads were produced mostly from local raw materials. White beads were made from clay, shells, ivory, or bone. Black and blue beads were made from iron, charcoal, seeds, clay, or horn. Red beads came from seeds, woods, gourds, bone, ivory, copper, or brass. When late in the nineteenth century, great quantities of brightly colored European glass beads arrived in Southeast Africa, beadworkers replaced the older beads with the new materials and began to use more elaborate color schemes. Currently, dense, opaque glass beads with no surface decoration and a naturally smooth finish are preferred.